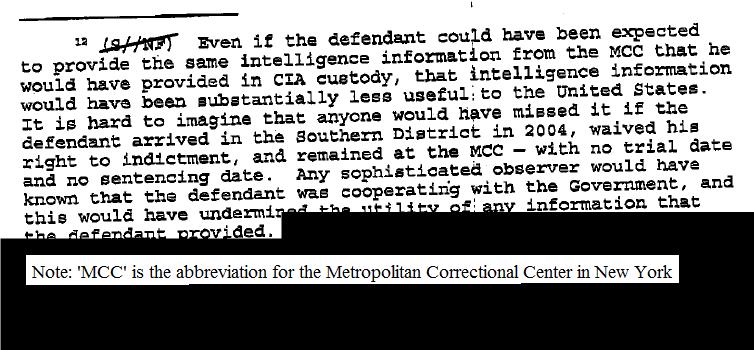

Fn 12 on page 59 of the DOJ’s December 18, 2009 rebuttal to Ghailani’s Speedy Trial Motion to dismiss his case in federal court. Click to enlarge

In their Wall Street Journal op-ed today, David B. Rivkin and Marc Thiessen understated the significance of the Bush doctrine arguments filed on December 18, 2009 by the Department of Justice and used to rebut the Speedy Trial Motion to dismiss the federal case against Ahmed Ghailani. Surely U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara did not file contrary to the direction of Attorney General Eric Holder.

Mr. Bharara is no doubt a dedicated public servant. I have great personal faith in his abilities, loyalty to our Nation, and willingness to do all that he can to successfully prosecute Ahmed Ghailani to the fullest extent of the law. That said, Ghailani is President Barack Obama’s canary for the federal prosecution of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, his 9/11 co-conspirators, and perhaps 40 more detainees currently being held at Guantanamo Bay. For the criminalization of the war against terror to succeed, Ghailani’s motion must fail. It is ironic and insidious that Obama and Holder must first defend what they seek to destroy:

On Dec. 18, 2009, days before the Christmas attack, the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, Preet Bharara, made a secret filing in federal district court that was aimed at saving the prosecution of Ahmed Ghailani, another al Qaeda terrorist. Ghailani is facing charges for helping al Qaeda bomb U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998. Ghailani argues that those charges should be dropped because lengthy CIA interrogations have denied him his constitutional right to a speedy trial.

Mr. Bharara, on behalf of the Justice Department, filed a memorandum with the court stating that Ghailani’s claims are dangerous and off the mark. Interrogating terrorists must come before criminal prosecution, he wrote in language so strong that even a redacted version of his filing (which we have obtained) serves as a searing indictment of the administration’s mishandling of Abdulmutallab.

“The United States was, and still is, at war with al Qaeda,” Mr. Bharara argued. “And because the group does not control territory as a sovereign nation does, the war effort relies less on deterrence than on disruption—on preventing attacks before they can occur. At the core of such disruption efforts is obtaining accurate intelligence about al Qaeda’s plans, leaders and capabilities.” … READ THE REST

Review again the image above and think about Flight 253 bomber Umar Farouk Abdulmuttalab. Then read this fuller excerpt from the DOJ’s rebuttal. It begins with the last paragraph on page 46 (B. Discussion) and runs through the partially transcribed paragraph on page 50. (Except where clarification was needed, citations and footnote numbering were omitted from this transcription):

First, the Government’s interest in protecting national security justified the delay in this case. The Supreme Court has stated that is “‘obvious and unarguable’ that no governmental interest is more compelling than the security of the Nation.” If vindicating the Government’s interest in, for example, presenting a more effective case by seeking to persuade a co-defendant to testify against the defendant is a “valid” reason for delay, it follows that this most compelling of interests is “valid” as well.

Indeed, delay is more justifiable in this case than when the Government delays a trial to persuade a co-defendant to testify against the defendant (an in Vassell). In both cases, the defendant’s trial is intentionally delayed by the Government. But it is only in the Vassell-type situation that the Government delays the proceedings in order to put the defendant himself in a worse position at trial. The possibility that the delay will harm an individual’s defense at trial is the core concern of the Speedy Trial Clause, and the Vassell-type situation skirts close to this concern in that situation, then surely it may be put off in a case such as this — when the purpose for the delay was not to enhance the chances of convicting the defendant, but rather to obtain information that could be used to prevent future terrorist attacks against the nation by incapacitating others…

The defendant attempts to discredit the importance and relevance of national security in this case by calling it “an intentionally amorphous concept that can fluctuate depending on the specific aims that the Government seeks to protect.” But, however vague or overstated the invocation of national security could conceivably be in other contexts, there is nothing “amorphous” about the concept as applied here, and no question that the strength of the Government’s interest was at its zenith in this case. The defendant was a longstanding al Qaeda terrorist, and al Qaeda is the group responsible for the brutal murder of thousands of American citizens here and abroad. The United States was, and still is, at war with al Qaeda. And because the group does not control territory as a sovereign nation does, the war effort relies less on deterrence than on disruption — on preventing attacks before they occur. At the core of such disruption efforts is obtaining accurate intelligence about al Qaeda’s plans, leaders, and capabilities. [emphasis added mine]

In these circumstances, the Executive Branch’s decision initially to treat the defendant, a foreign national captured abroad in an al Qaeda safe house after a 14-hour gun battle, as an intelligence asset — to detain him abroad in order to detain vital, real-time intelligence about al Qaeda — warrants considerable deference. As the Supreme Court explained only last year:

In considering both the procedural and substantive standards used to impose detention to prevent acts of terrorism, proper deference must be accorded to the political branches. Unlike the President and some designated Members of Congress, neither the Members of the Court nor most federal judges begin the day with briefings that may describe new and serious threats to our Nation and its people. The law must accord the Executive substantial authority to apprehend and detain those who pose a real danger to our security.

Boumediene; see also e.g. United States v. Moussaoui … cf. Central Intelligence Agency v. Sims.

The pdf of the DOJ’s rebuttal is in two parts, here and here, if you wish to download it.