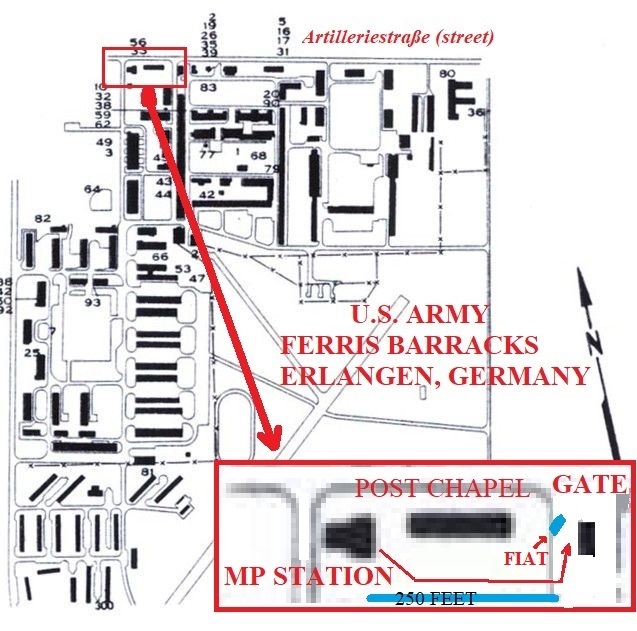

Map of Ferris Barracks, circa 1975, with an enlargement and graphics added.

May 1975

U.S. Army base, Ferris Barracks, Erlangen, West Germany

The two unarmed Unit Police (UP) soldiers called the Military Police (MP) Desk a block away and reported a “Blond-haired white male driving an older tan Fiat” had twice rolled slowly down the street outside and passed the Main Gate, staring hard at them. (The other gates were closed after midnight and MPs often checked IDs for suspects after major crimes. Criminals looked carefully before attempting to enter there.)

Further, they reported the rear license plate matched the ‘Be on the lookout’ BOLO alert that I had sent them, except the last two numbers were reversed; they read 37, not 73.

Bingo!

But I had a problem: My three MP patrols were miles away on cases, investigating that rape outside a disco bar, a stabbing in a Gasthaus up north, and a fatal traffic accident on the autobahn.

I told our awesome and ancient interpreter, Mr. “Senior” Wasner, to lock the front door and then call the German Police. Then I tossed the arms room’s keys into the evidence safe and locked it, grabbed my flashlight, and went out the back. I once ran the 100-yard dash in high school in 10.6 seconds; the gate was a mere 75 yards away.

I ran fast past the Post Chapel. Yet my fear that I had missed catching him subsided for ahead of me, beyond the fence line, I could hear the faint sound of a vehicle approaching on Artillerie Strasse.

As I reached the street, I slowed to a walk about 40 feet from the gate shack. The suspect turned slowly left into the gate, with his speedy Fiat in neutral. The driver, Sergeant “W” (name changed), saw me and gunned his engine, grinding the gear. But he would soon hit the clutch and run me down out there directly in front of him.

He must have noticed my Army-issued .45 Caliber Model 1911 pistol was aimed his way. Or perhaps he saw the MP armband on my left shoulder and heard me shouting “Halt or I’ll shoot” for he turned the wheel hard to the right and hit the 18-inch-high painted stone curb.

His car conked out.

The UPs in the gate shack had dived for cover. I talked “W” out of his car, handcuffed him, locked the car, and told them to not let anyone other than MPs and GPs touch it.

I perp-walked him through the MP station backdoor less than 3 minutes after I had left there and secured him in the detention cell. After unlocking the front door, I read him the standard legal rights warnings, which he waived. The collected evidence was damning. He confessed but then pled not guilty at his arraignment to charges of Rape and Assault with Intent to Commit Grievous Bodily Harm.

However, it was only zero-300 (3 AM). I had eight cases to type into the MP blotter, three Serious Incident Reports (SIR) to have a patrol co-op to the Nuremberg MP Station and Provost Marshal’s Office, and an Army Master Sergeant with four slashed tires sleeping in his car blocks away waiting for me to send a “spare” patrol.

No problem. I was done by change-of-shift at zero-800. I went back to the barracks, ate breakfast, and hit the rack.

At noon, Sergeant First Class (SFC) “D.C.”, my Platoon Sergeant who was from North Carolina, flipped my mattress and me onto the barracks room floor.

“The MP Station Operations Sergeant wants to see you – right now. Throw on some civvies. A patrol is waiting outside.”

No, I had not forgotten anything, except that SFC “B” was “by the book.”

I was not expecting coffee and a medal, but a chewing out and threat to have me court-martialed for “going AWOL” from the MP Desk for three whole minutes was a bit much. I took it at the position of attention, requested permission to obtain a lawyer before answering his questions, and was dismissed.

I returned to report to “D.C.” – as ordered – and briefed him. He was livid and put me on the phone with First Sergeant Repass, our MP Company’s “Top” Soldier. The latter was former Infantry, former Special Forces, and a highly decorated Vietnam Veteran.

Repass said, “Great work! Get some sleep. I will speak with SFC Black.”

I slept like a baby and was back on the MP Desk that evening. “W” went to prison at Fort Leavenworth. Sometimes you have to improvise. I was a mere Specialist Fourth Class – with all of fifteen months in service – and was filling in on the Desk for they were short of Sergeants, and later awarded an Army Commendation Medal.

Good times.

Epilogue

SFC Black was white and a decent guy, but he was difficult to deal with at times. He soon retired. Before leaving, he invited me over to his house for lunch where his wonderful half-black and half-German wife served us a fine meal. He went on to become a successful black-and-white photographer.

His equally stringent replacement, the brilliant and funny Staff Sergeant Thomas Jackson – who was black and no one’s Uncle Tom – “tolerated” me for a few weeks until new Sergeants arrived and were assigned to the MP Desk.

I went back to road MP patrol duty where I belonged.

Sergeant “W’s” court martial panel could have sentenced him to life in prison for raping a 16-year-old drunk German girl in that parking lot. Yet he came face-to-face with his own mortality and to rest facing God’s house that dark May night.

The defense cross-examined none of the prosecution witnesses – not one. The victim testified against him yet asked the jury to show mercy to her attacker, to not sentence him to life. She added that she would live, grow, find love, and dance again. There was not a dry eye in the courtroom – not one. He was the sole witness for the defense, read a statement expressing deep remorse to the girl, and then repeated his confession to the jury. The jury convicted and sentenced him to 6 years.

The Almighty will render final judgment.

—

Afterword

fiat (n.) 1630s, “authoritative sanction,” from Latin fiat “let it be done” (used in the opening of Medieval Latin proclamations and commands) … In English the word also sometimes is a reference to fiat lux “let there be light” in Genesis i.3. … Perhaps Sergeant W came to see the light that dark night north of Nuremberg.

Updated May 31, 2022