Christmas Day of 1975 is hard to forget. Children crying, followed by a horrific traffic accident, and then an angry man walking towards me with a knife did not make the season bright.

All the businesses and bars were closed. Road traffic was exceptionally light. It was my second Christmas in the U.S. Army and second straight Christmas Day on patrol in Germany while serving there as a Military Policeman. My patrol partner was fairly new, and just 19 years old. We were working the 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. dayshift. There was no second MP patrol on duty. All the married MPs assigned to my platoon had the day off. In fact, half the platoon was on administrative leave (not counted against accrued leave) for six days. The rest of us would get six days off over the New Year’s holiday; we were looking forward to it.

The good news was the mess hall (Army dining facility) was open from 8 to 4, and Christmas dinner was to be served from noon until closing time, or so they said. We ate breakfast there as soon as they opened.

Then it started.

First, a fight broke out in a 2/81 Armor Battalion barracks. The unit’s Company Commander and First Sergeant had just arrived and were waiting for us outside. They beckoned us to follow them in. Inside, we found twenty guys in the ground floor hallway in a shoving match. I blew my police whistle and the First Sergeant shouted, “Attention!” The troops complied and lined up with their backs against the hallway walls. The affray was over someone allegedly stealing someone else’s beer. At the Commander’s request, we left it to him to investigate the incident.

We were soon dispatched to a domestic disturbance in the family housing area. Their neighbor had reported continuous screaming and crashing noises. They were still arguing loudly when my partner and I pounded on the door. The wife answered. “We need to come in, ma’am,” I said. We entered. The tree had been knocked over. Her husband, a Soldier, was picking up the pieces of a broken toy and a few plates. We could hear children crying down the hall.

I asked, “Are the kids okay?”

The husband calmly replied, “Yes. No one is hurt. We had an argument over me buying her dishes and the wrong toys for the kids for Christmas. That’s all.” I had my partner accompany the woman towards the kids’ bedroom. (He knew to stay out in the hallway where we could see each other.) After a few minutes, she brought their two kids (5-year old twins) out to the living room. They ran to their father, embraced him, and started bawling again.

“Please don’t arrest my daddy,” the little girl cried.

No government property had been damaged. We observed no injuries. And the argument was over. We took the identifying information of the Soldier and his family. I advised him that a journal entry would be made (a non-criminal report). His unit would be notified of the disturbance and we would write up our observations for his commander’s information. The kids started playing with their gifts. The wife and husband hugged each other and laughed. We departed.

It was just passed 10 o’clock in the morning. What next, we wondered.

It was cold, just above freezing, and raining. No sooner had we finished our written statements at the MP station when, around 11 a.m., the Desk Sergeant got a call from the German Police about a minor traffic accident 10 miles away near Herzo Base (an Artillery base).

We were almost there when the Desk Sergeant radioed, “Disregard last (mission). Proceed to the Frauenaurach northbound exit to the autobahn. Traffic accident with injuries. Code three.”

German Police patrols and ambulances were on the scene when we arrived several minutes later. It was bloody. A truck with trailer, a Soldier’s car, and two cars driven by German civilians had plowed into each other on the icy exit ramp. Seven adults, including a GI and his wife, and two German children were being evacuated with life-threatening injuries.

It took hours to investigate and clear the scene. We arrived back at the MP station after 3:30 p.m.

We had hand-written most of the MP report, created a rough sketch, completed the separate traffic accident report form, and drafted an investigator’s statement while at the scene. The Desk Sergeant quickly reviewed our work to check for answers he needed for the Serious Incident Report (SIR) that had to be delivered ASAP by the on-coming swing shift MP patrols. Then he told us to proceed to the mess hall (three blocks away) as it would be closing in 15 minutes. We were to return and finish the paperwork after chow.

We arrived at the dining facility at ten minutes to four, and grabbed trays stacked by the door. All the food, except for some sausage patties and bread, had been removed from the chow line. The last three remaining diners had passed us going out as we entered. Behind the serving counter was the Mess Sergeant, the NCO-in-Charge (NCOIC).

This guy was trouble.

Two months earlier, he refused to serve breakfast to two on-duty Military Police. He had orders, signed by the Post Commander, saying no weapons were to be carried into the mess hall. The first to encounter him that day argued the order did not apply to armed MPs, but only to Soldiers who had been issued them for the purposes of training and maintenance. An argument ensued. The Post Chaplain, a Major who was dining there, overheard the shouting match and intervened. The MPs left. The Mess Sergeant got chewed out that morning, personally, by the Post Commander; his order clearly stated it did not apply to on-duty MPs.

“We’re closed,” the Mess Sergeant snapped at my partner and me.

“Sergeant, it is 1550 hours (3:50 p.m.) and you were supposed to stay open until 1600,” I replied in an even voice.

“The line is closed. My servers have all left. You’re out of luck,” he said, and then he laughed.

I replied, “Sergeant, please give us a couple of plates of leftovers and we’ll get out of your hair.”

“Get out of my mess hall, Specialist Sumner,” he said. (We wore nametags on our uniforms.)

My young partner flung his tray, frisbee-style, towards the tray-return window off to our left and fifty feet away; it landed a few feet short. He turned around and walked out.

The Mess Sergeant then almost made his last mistake.

He became enraged, ran to the far end of the serving line, and came around it with a long and obviously very sharp carving knife in his hand. He slipped and nearly fell on the freshly mopped floor. It slowed him down. But he came right at me, while looking towards the door.

I stepped back, grabbed the pistol grip on my loaded .45, and shouted, “Halt. Military Police!”

His eyes flashed to my right hand and he stopped dead in his tracks.

“Merry Christmas, Sergeant,” I said. Then I placed my tray on the counter and backed out. He did not follow us. We returned to the MP station and briefed the MP Desk Sergeant about the incident.

“You’re getting soft in your old age, Specialist Sumner,” he said. (I was to turn 23 in a few weeks). He added, “You came back without a slice of pie for me and without Sergeant First Class Cook in handcuffs. Go finish the paperwork. I’ve some calls to make.”

We went off duty at 6 p.m. and returned to the barracks. At least there were some store-bought cold cuts and cold beers in the refrigerator.

Our Platoon Sergeant entered my barracks room five minutes later without knocking. “Change clothes and be downstairs in five minutes. You are having dinner at my house. I’ll tell your partner. No arguments,” Sergeant First Class Dan French said.

A few years earlier while doing field training prior to what would have been his second combat tour of Vietnam, someone recklessly set an opened can of gas near a hot field stove near where he was standing. It blew up. French spent the next year and a half in hospitals due to burns to half of his body. He lost his hearing in his right ear, some of it in his left, and wore a hearing aide.

He had been our Platoon Sergeant for several months. Most marked him as a pushover. Me, I thought he was a little too easy on us. One not too bright MP (not me) dubbed him The Ear That Could Not Hear. One day, said Soldier said it once too often and this time while standing to French’s left; that Soldier got busted to PFC for Insubordination.

Mrs. French rolled out a feast. They had eaten a bit earlier, yet there was plenty left for two “starving” and thankful GIs. We had a blast watching his kids play with their treasures. They had been up and at it since dawn. Then we loaded up on desserts.

Around 9, she took the kids to get ready for bed. He asked us about our day, so we told him.

SFC French looked straight at me and said, “I know what you are thinking. A doctor at Walter Reed advised me to dig two graves before looking for revenge, including one for myself. Just before Christmas the second year, just before I got released to return to duty, the guy who set that gas can there came to see me in the hospital. He brought along his wife, three kids, and presents for my entire family. We all spent the holidays together. And we remain friends.

“That Mess Sergeant is a jerk, a mini tyrant who runs a mess hall. You are a good guy, Sumner, and better than he’ll ever be. And you know what? You won’t have to go looking for him. He’ll screw up and his Army career will be cut short because some MP will be there to catch him.”

I replied, “You and your family made this a very Merry Christmas for us after a really tough day. Many thanks, Sergeant. I’ll take your smart advice as a standing order.”

Epilogue

We said our goodbyes. SFC French drove us back to the barracks. We went back to work the next day. I saw that Mess Sergeant in the mess hall from time to time, but we never spoke.

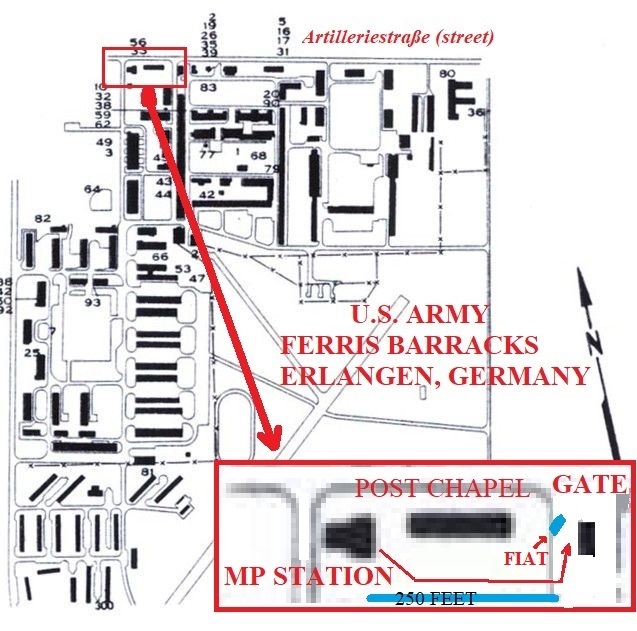

The following February, at about three in the morning on a back road leading to Ferris Barracks, another on-duty MP and I saw a car ahead of us weaving wildly, repeatedly crossing the center line, and then sharply returning to its lane. It had license plates on it indicating it belonged to a GI. We hit the blue lights.

Instead of pulling over, he made a 90-degree right turn off the road and slammed into a frosted and snow covered pine tree. It was him.

SFC Cook was a bit bruised, very drunk, and arrested. His Battalion Commander revoked his license, removed him from the promotion list, fined him heavily, relieved him of Mess Sergeant duty, and transferred him to assist at a different mess hall. Happy New Year!